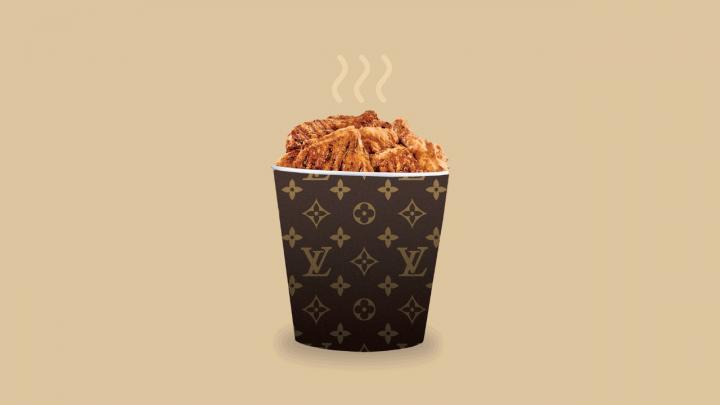

World famous luxury brand Louis Vuitton (LV) was awarded 14.5 million won ($12,500 USD, or 83,000 RMB) this April in a lawsuit with a Seoul fried chicken restaurant named “Louis Vuitton Dak”. The restaurant was first sued in September for Unfair Competition – using a name or packaging so similar to another brand that consumers think they are purchasing from a different company. Explore the intricacies of Brand Naming and intellectual property risks with Labbrand.

This claim is fairly common across Asian markets, as some brands use copycat verbal or visual identities to benefit from an immediately strong Brand Equity that is recognized globally. In fact even after the lawsuit, the restaurant owner Kim changed the brand name to “chaLouisvui Tondak” – not exactly a reversal from the first copycat name. The courts slammed Kim with yet another fine and forced him to change the brand name for a second time.

It seems that even with regulatory bodies doing their utmost, no foreign brand is completely immune to the potential consequences from a knockoff. For foreign brands that are interested in global success, the question then becomes what can foreign brands learn from this IP case?

As naming experts in one of the most complicated IP systems in the world, Labbrand is no stranger to evaluating legal risk. In this piece, we’ll take a look inside the potential logic of creating a rip-off brand, and how foreign businesses entering the Chinese market can mitigate the potential risks.

What Was Kim Thinking?

As the start-up culture continues to thrive in Asia, entrepreneurs are constantly seeking strategies to outshine their competitors. Utilizing the power of effective brand naming becomes crucial. Leveraging LV’s brand and logo for your startup can immediately capture consumer attention and curiosity, leading to broader recognition as your business opens its doors.

In certain Asian countries, this initial advantage can significantly impact a business’s success. For instance, when China initiated its economic reforms in 1978, a wave of entrepreneurial spirit swept from rural to urban areas, and only those who swiftly adopted and adapted their brand strategies experienced commercial success. Agility and innovative brand naming are deeply ingrained in the business culture of many Asian countries.

From Kim’s perspective his small-scale fried chicken restaurant was in no way noticeable to the international French luxury brand, so the risk of any legal action was low.

If the eatery was to come under legal scrutiny, it would be an output of its size or popularity – which means the goal of quick growth was already achieved. Moreover, the fine amount for such cases is not very large.

In the most extreme case, Kim’s restaurant may be asked to halt all its infringement activity. However, upon eradicating all infringed products and packaging and changing the logo, the eatery may return to normal operation. Long term legal consequences are mild.

The most cyclical part of Kim’s situation is that the more coverage LV Dak gets, the more its awareness grows. At the time of this writing there were dozens of related articles visible on some of the most globally-recognized publications, including Yahoo, Vogue, Mashable, and NYmag.

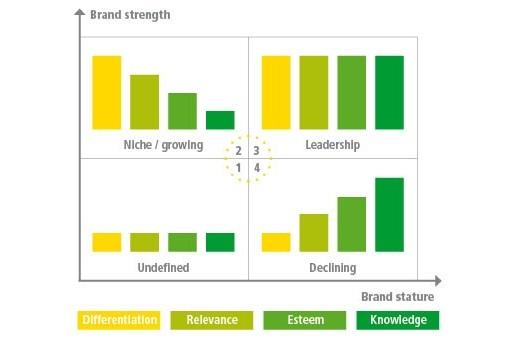

But growth in awareness does not necessarily mean a growth in brand equity. As we know from our Four Pillars of Brand Equity model, awareness – a sub-component of Relevance – cannot support a brand on its own. When a brand has high Relevance but no Differentiation, it lacks Brand Strength which is the foundation for long-term brand success. Furthermore as a copycat, the brand’s Esteem and Knowledge and unlikely to develop further, resulting in comparatively low measures of Brand Stature. A brand that focuses on copycatting will develop no long-term advantage and will not thrive in its market.

This analysis is likely lost on the fried chicken restaurant, which has no ambitions of expanding beyond a “blip” in the market or building long-term brand equity.

So while copycat brands do exist, they are insignificant in the long term. Instead let’s focus on how to protect the brands that have created powerful Brand Equity on their own.

How can Foreign Brands Protect Themselves?

While things will return to “business as regular” in Seoul, the consequences for Louis Vuitton are more serious: there is now a segment of consumers around the world who will think of fried chicken when they hear the name LV, likely not the association the French brand is seeking. Assuming the proper registration protocols are followed, how can foreign brands best handle and protect themselves in cases of IP Theft?

Plan ahead. As a brand manager you hope you never have to encounter the ugly world of IP theft, but if you do, you must be well prepared with a plan ready to be deployed. Effective brand naming plays a crucial role in safeguarding your intellectual property. One of the most important things about IP situations is the ability to quickly identify out a threat and to just as quickly remove it.

As such, think about how you would handle the situation – who will be the project manager, how aggressive the firm will be, what channels will be used to neutralize the threat, and what law partner is best suited to handle the situation. Have a clear process in place and a partner that is ready to move quickly.

A recent report published by UC Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Law and Society revealed that 12 new international law firms were established in China every year between 1992 and 2012, and that an optimal business model that included an outpost office involved in an international partnership. The conclusion? Stagnation of foreign firms can be an output of China’s unique political influence in the legal services market, prescribing the need for partnerships between Western and local partners.

Legal systems differ by countries all over the world, and each country has its own specific rules and regulations that can be difficult to follow. No law partner will understand these processes better than one that is local to the market.

A common misconception for foreign brands is to focus on the Court system, as it is the most relatable to a western-style solution. However, in China the complex dimensions of the court system can make it more inaccessible.

If a similar case of Unfair Competition had happened in the Chinese market, for example, the brand owner would usually complain to the Administration for Industry and Commerce (AIC) about the trademark infringement. The AIC will order the infringer to stop the act immediately, sequester all the infringing products, and remove the signboard with the infringing trademark or logo. More owners prefer to protect their rights through the AIC as it achieves roughly the same solution as the Courts, with less cost and time involved.

Takeaways

If a company wants to copy your brand’s name or design, prevention options are limited to proper registration in every relevant class (and some irrelevant classes), protecting property both within China and in Macau, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The next steps are where many brands fail:

A Labbrand Group Company © 2005-2024 Labbrand All rights reserved

沪ICP备17001253号-3* Will be used in accordance with our Privacy Policy

To improve your experience, we use cookies to provide social media features, offer you content that targets your particular interests, and analyse the performance of our advertising campaigns. By clicking on “Accept” you consent to all cookies. You also have the option to click “Reject” to limit the use of certain types of cookies. Please be aware that rejecting cookies may affect your website browsing experience and limit the use of some personalised features.