In the dynamic landscape of China’s rapidly growing economy in 2010, marked by its ascent to the position of the world’s second-largest economy, numerous questions arise for businesses and brands seeking success in this flourishing market. For foreign companies and products aiming to capture the affinity of Chinese customers, the challenge is significant. Additionally, the fate of foreign brands inevitably acquired by Chinese capital raises curiosity. Amidst these queries, one notable puzzle is the relatively limited global presence of Chinese brands. Delving into the narratives of these brands, exploring their unique journeys and brand stories, provides insights into the intricate dynamics of China’s evolving economic and business landscape.

Delving into the intricate tapestry of China’s brand landscape in 2010, Labbrand revisits the year’s most captivating and significant brand events. This curated list spans a diverse array of brands, encompassing both new and established, Chinese and foreign entities. Each entry is accompanied by a concise summary elucidating the events and their significance. By exploring these brand stories, we unravel the multifaceted narratives that shaped the Chinese business terrain in 2010, shedding light on pivotal moments and trends that continue to influence the brand landscape.

What Happened

China’s leading sporting goods brand entered the US market in January with little fanfare. But by opening its first store in Portland, Oregon, near Nike headquarters, Li-Ning was clearly sending a shot over the bow of the global leader. The Chinese brand was also signaling its intent to continue global expansion, with stores already open in Hong Kong and Singapore and celebrity endorsements from the likes of Shaquille O’Neal.

In June, Li-Ning redesigned its 20-year old logo, which was widely regarded as little more than a copycat attempt at Nike’s ubiquitous Swoosh. The new, two-part logo can also be interpreted as lowercase letters L and N, which imbues the mark with more meaning for readers of English (or similar alphabet-based languages). At the same time, Li-Ning changed its tagline to “Make the Change” from “Anything is Possible,” which, while introduced two years earlier, was very similar to the current Adidas tagline, “Impossible is Nothing.” (Adidas is also headquartered in Portland.)

To round out a big 2010, Li-Ning launched a comical TV commercial in the US to announce the brand’s arrival to America.

Why It Matters

In the short term, Li-Ning may not represent a significant threat to leaders like Nike and Adidas on their home turf. Aside from initial curiosity, Westerners won’t instantly warm to a Chinese sportswear brand, despite the fact that they assume their Nikes are already made in China. Interestingly, having a presence in the United States may do more to help Li-Ning dominate in China and Asia, where selling to Westerners is likely to be seen as an indicator of quality and prestige.

But more importantly, Li-Ning is on the forefront of a slow-rolling wave of Chinese brands that will expand outside of China this decade. Today, despite excitement—and fear—about coming Chinese economic dominance, asking non-Chinese people to name their favorite Chinese brands is like asking them to name their favorite Chinese NBA players—easy to name one, two if you’re really in the know, but it gets a lot harder after that. Because of Li-Ning, Tsingtao, Haier, and a handful of other brands, this will change soon. Other sportswear brands Anta Sports, Peak Sport, and Xtep are already sponsoring major athletes and events around the world. In the transportation sector, companies like China Railways Group, King Long, BYD, and Chery all have plans to do business and grow awareness outside of China. Even the luxury market will be introduced to new Chinese trendsetters like NE Tiger, which has studios in the US, Europe, and Russia.

Li-Ning’s USA market entry could have other far-reaching consequences due to the brand’s decision to flaunt its Chinese-ness rather than downplay it. If Li-Ning is able to poke a hole in the cliché that everything made in China is poorly constructed, it will open doors for countless other Chinese brands with global ambitions.

What Happened

In March, Ford Motor Company sold Volvo to Zhejiang Geely Holding Group for over 1.5 billion USD. The holding company is parent of Geely Automotive, one of China’s largest non-state-owned automotive manufacturers. However, both Volvo and Geely stressed that the companies would be kept separate and that, in the words of Swedish deputy prime minister Maud Olofsson, Volvo’s “brand will still be Swedish.”

Why It Matters

For Ford, one of the United States’ struggling “Big Three” auto makers, this sale provided some much needed capital and an opportunity to renew focus on core brands. For Volvo and Geely, however, the acquisition is uncharted territory in more ways than one. Despite Geely Chairman Li Shufu’s insistence that “Volvo is Volvo and Geely is Geely,” it remains to be seen whether a brand recognized for safety and reliability can survive the ‘made in China’ stigma. If so, the two companies still face the significant challenges of reviving an unprofitable brand in the West and restructuring in China, all while merging corporate cultures and maintaining product quality.

But beyond the single deal is the more general statement it makes about the increasing acquisitiveness of Chinese companies and a global power shift in the automotive industry. Other significant Chinese investments in this sector include the Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation’s (SAIC) joint ventures with GM and Volkswagen and the Beijing Automotive Industry Holding Company’s (BACI) joint ventures with Jeep and Daimler-Benz. Furthermore, expansion in North America and Europe is rumored for Chinese manufacturer BYD and others. Chinese companies are not limiting themselves to the auto industry, either, with significant acquisitions and investments in consumer electronics (e.g., Lenovo), oil and gas, financial services, and more.

What Happened

137-year old American apparel company Levi Strauss & Co. launched its first brand to debut outside the US in August of 2010. Dubbed dENiZEN, the lower-priced sub-brand is targeted at 18 to 28 year-old men and women in Asia, and specifically China, where Levi’s has been operating for 10 years. Levi’s hopes dENiZEN will present a more affordable entry point for Chinese consumers, and has emphasized the brand’s accessibility by using amateur models—“everyday people”—in runway shows and advertisements. dENiZEN first launched in Shanghai, with plans to expand to Beijing and other cities.

Why It Matters

Certainly, there’s nothing new about the arrival of foreign brands in China, where KFC has over 3,000 restaurants and other foreign brands like Gap and Carl’s Jr. are arriving every day. Product localization is also nothing new, as evidenced by Lay’s Hot & Sour Fish Soup potato chips, Starbucks’ Chinese tea and mooncakes, and BMW’s local 5 Series, with extra legroom in the back to make wealthy Chinese more comfortable sitting behind their chauffeurs.

But according to their website, dENiZEN is “the first brand from Levi Strauss & Co. ever to debut outside of the USA.” Obviously significant for Levi’s, the creation of new sub-brands specifically for China is also a relatively new trend. In 2004, KFC introduced East Dawning (东方既白), a Chinese-food, quick-service restaurant created exclusively for China. Creating a new brand can also be a unique strategy for market entry, as Taiwanese smartphone giant HTC is attempting with its Chinese subsidiary, Dopod (although the success of this move is yet to be determined).

For Levi’s and dENiZEN, the current challenge is to enhance relevance to Chinese and other Asian consumers without squandering existing, positive associations with the Levi’s brand. From a brand portfolio standpoint, how will this sub-brand fit with other global Levi’s brands (including Dockers and Signature) so that it gains from being a member of a prestigious brand family while minimizing potential damage to more premium brands? If dENiZEN is intended as an entry point, how will Levi’s eventually move customers toward the group’s more expensive brands? The future success of dENiZEN rests partly on answering these questions effectively. Regardless of Levi’s success, however, other foreign brands hoping to succeed in China should study this approach carefully.

What Happened

French luxury giant Hermès helped fund the creation and launch of Shang Xia, a new luxury brand designed and manufactured in China. Aside from owning over 75% of the company, Hermès’ specific involvement is not yet clear. The first Shang Xia boutique is in Hong Kong Plaza, a luxury shopping mall in Shanghai.

The brand’s products are slightly more affordable than those of Hermès, which has 20 stores in China already. Also, Shang Xia is positioned as a Chinese brand, led by a designer from Shanghai (although trained in France), with products—such as tea sets, apparel, and jewelry—made from local materials and designed based on traditional Chinese craftsmanship.

Why It Matters

Whereas dENiZEN (above) is priced for Chinese consumers, Shang Xia is designed for them. The new brand is therefore trying to avoid, rather than benefit from, perceptions of foreignness. But in a country where foreign brands are still widely regarded as higher quality than domestic brands, Hermès’ support could act as a double-edged sword, buttressing the brand’s reputation as luxurious and well-made while hurting its chances of being perceived as Chinese. This balancing act—how best to weight local relevance against the prestige that may come with foreign provenance—is critical for any foreign brand doing business in China. Brands doing business internationally must also acknowledge the strategic importance of staying true to their core idea and promise.

Shang Xia indicates that Hermès is willing to take a less conservative approach to the China marketplace, suggesting its recognition of the market’s potential for growth. Rather than importing brands or localizing products, more and more foreign companies will be creating entirely new brands from scratch or through well-crafted partnerships. For Shang Xia to effectively position as a homegrown Chinese luxury brand, however, it will have to convince Chinese consumers that it is much more than a discounted version of Hermès and demonstrate its roots in Chinese heritage and craftsmanship. In doing so, it faces the considerable hurdle of helping define high-end Chinese design—what it looks and feels like, how it fuses luxury and traditional craft, and what, if anything, it has to do with foreign notions of luxury.

What Happened

State-owned Shanghai Jahwa Group is China’s largest cosmetics company and owner of Herborist, a natural-ingredient cosmetics line that has recently exported products to Europe and the USA. This past summer, the group re-launched one of its own iconic legacy brands, previously known as Shuang Mei (双妹). The brand has a new name, Shanghai VIVE, but everything else about it looks old, nostalgic, retro. Shanghai VIVE’s logo, packaging, advertising, and scents—even the location of its first store in the newly renovated Peace Hotel—are all reminiscent of Shanghai’s 1930s glory days. With premium pricing and plans for more than 20 new stores over the next three years, the resurrected brand’s soaps and perfumes will go head-to-head with dominant foreign brands.

Why It Matters

Shanghai VIVE will test consumers’ appetites for Chinese luxury cosmetics—a market currently ruled in and outside China by brands such as Estée Lauder, Dior, Lancôme, and Clarins. The decision to position the brand as retro chic will also be tested, as the attempt to capitalize on global fascination with China and Shanghai’s revitalization could be perceived as trendy and exploitative rather than classic and reverential.

Shanghai Jahwa Group is not the only company bringing back old Chinese brands, however. Other recent examples include Warrior and Feiyue sneakers, Red Flag limousines, and Forever bicycles. These throwbacks represent a growing desire to revive old Chinese brands, some of which lost out to foreign brands during China’s opening up in the 1990s. Now, as Chinese entrepreneurs and consumers are increasingly empowered, both figuratively and literally, a continuing resurgence of fallen-but-not-forgotten Chinese brands can be expected. For brands like Shanghai VIVE to make it this time, they’ll have to be able to count on growing confidence in Chinese brands and China alike.

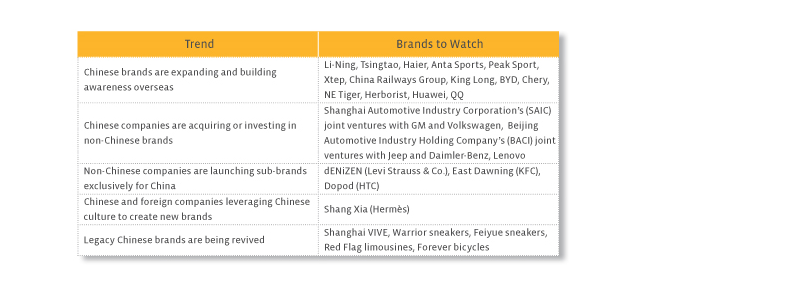

These are just five of the past year’s most interesting brand stories in China. Each of them demonstrates a broader trend that will continue in the near and long term. The following chart summarizes overarching trends listed herein and some representative brands to watch in 2011.

Underlying these trends are the obvious common threads of China’s rapid economic growth and a rising appreciation of the significance of the Chinese marketplace. A more subtle but equally important through-line is a changing mindset toward China’s role in globalization.

China is reveling in the radiance of a triumphant trio—the Beijing Olympics, Shanghai’s Expo, and the Asian Games in Guangzhou. These monumental spectacles not only stirred national pride but also broadened the global perspective of the average Chinese individual. Amidst the lingering financial downturn in the West, a surge in optimism is reshaping viewpoints, steering away from the erstwhile “foreign is better” paradigm. This newfound confidence becomes the canvas for bold business maneuvers and daring branding initiatives, potentially ushering in unforeseen mergers, the rise of more distinctive Chinese brands, and ultimately, genuine innovation from China—adding compelling chapters to the ongoing narrative of brand stories.

A Labbrand Group Company © 2005-2024 Labbrand All rights reserved

沪ICP备17001253号-3* Will be used in accordance with our Privacy Policy

To improve your experience, we use cookies to provide social media features, offer you content that targets your particular interests, and analyse the performance of our advertising campaigns. By clicking on “Accept” you consent to all cookies. You also have the option to click “Reject” to limit the use of certain types of cookies. Please be aware that rejecting cookies may affect your website browsing experience and limit the use of some personalised features.