Feb 13, 2025

For years, Chinese brands have fought an uphill battle in the U.S. with less-than-ideal country branding. While a “Made in China” stigma remains a hurdle for Chinese brands in the US, the tide is shifting—especially among younger consumers. Last month, in a collective release of pent-up frustration over a potential TikTok ban, Americans found themselves deep in the heart of the Chinese internet. It’s questionable whether Americans have intentions to stay on RedNote for the long term but ‘the RedNote effect’ may be indicative of a larger zeitgeist shift, onewith branding implications. Could this be the moment Chinese brands stop fighting against their origins—and start leveraging them?

Negative narratives about Chinese products have long dominated American discourse—claiming that they are lower quality, shamelessly dupe or knockoff other brands, are potentially made with unethical labor, or represent fast-fashion production that’s harmful to the environment. The “made in China” reputation is historied, while companies like Shein and TEMU have refueled it in recent years. For more advanced Chinese products, American consumers’ perceptions are often clouded by suspicion of IP theft, which would seem to fly in the face of the “innovative” reputation many Chinese tech brands typically enjoy in their home market. And of course, there’s the grievance that’s been most popular lately, that Chinese companies usher in national security threats. High-profile cases, including Huawei, Bytedance, and most recently, the Chinese AI app DeepSeek, have reinforced paranoia over Chinese brands among U.S. consumers and policymakers alike.

These negative stereotypes resonate differently for different generations of Americans—Gen X and boomers may fixate more on national security threats, while Gen Zs may care more about environmental concerns. Regardless of which storyline is more palpable, these negative sentiments remain hurdles for mainstream US shoppers buying Chinese products. If not banned outright, Chinese companies face further hurdles, often deep in the minds of American consumers. US shoppers might process some guilt or resolve pesky cognitive dissonance when they purchase Chinese brands. They may not be as inclined to brandish their purchase with pride and spark word of mouth (See Table 1). It’s no surprise that the dominant strategy from Chinese brands targeting US audiences has been through acquisition instead of growing a brand organically. With this strategy, connections to China are rarely incorporated in brand identity, with Chinese-acquired brands such as GE Appliances, Motorola, AMC Theaters, Volvo, Grindr, and the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City downplaying their Chinese ownership to consumers.

But now, China is in. At least among Gen Z consumers who are more likely to favor Chinese brands and purchase from them more frequently than the broader public. The ‘Rednote effect’ has made acceptance of China increasingly robust. The over half a million “TikTok refugees” who have found themselves on RedNote (also known as Little Red Book, RED, and Xiaohongshu) are shifting the consensus about China. There may be potential for Chinese brands to not only catch a new American consumer base but also present a brand image to Americans that capitalizes on Chinese origin.

Table 1:

Post-Purchase-Origin Emotional Meter: Is American consumer psychology shifting on China?

1. Guilt | A personal moral onus over purchasing a product from a certain origin

Internal monologue: “I feel bad that I supported the Russian economy by purchasing this vodka”

2. Shame | A self-consciousness about people finding out you purchased from a certain origin

Internal monologue: “I’m going to take off the tag that says ‘made in China’ so no one thinks I’m cheap”

3. Hesitation | Uncertainty or mild discomfort about the purchase origin, often leading to rationalization

Internal monologue: “TikTok might give my data to China, but I mostly just watch cat videos, and Instagram does the same thing anyway”

4. Indifference | Unawareness or disregard about the purchase origins or their perceptions

Internal monologue: “This chocolate is so good, I don’t care how it’s made”

5. Reaffirmed | confidence in the purchase due to its origin

Internal monologue: “This facemask is from Korea so I know it must be good”

6. Pride | a desire to show off the origin of the purchase

Internal monologue: “Let’s use the French wine when we host so people think we have taste”

7. Altruism | a personal moral fulfillment over purchasing a product from a certain origin

Internal monologue: “I got this coffee from a local female-owned café, good on me for not supporting big greedy corporations”

The shift to RedNote began as a reaction to TikTok bans and the need for a new entertainment fix, but the decision to migrate to a Chinese platform specifically was driven by layered motivations.

When TikTok users sought concrete proof of national security threats tied to the app, they were met instead with redacted documents and vague official statements. Meanwhile, Meta—despite its own national security controversies—played a significant financial and strategic role in advocating for the ban, fueling skepticism of anti-China rhetoric and reinforcing the view that American tech companies are no less problematic.

Adding to this skepticism was a viral exchange between TikTok’s Singaporean CEO Shou Zi Chew and US Senator Tom Cotton who spoke as if he did not understand the distinction between Singaporean and Chinese citizenship. This moment, already widely criticized for its ignorance and racial undertones, experienced a resurgence of virality in January 2025, reigniting collective disgust over a TikTok ban that seems fueled by Sinophobia. For many, it helped set the conditions for many Americans to embrace a more open-minded perspective toward China, including its products and brands.

So when TikTok was officially banned on January 19, 2025, people going through TikTok withdrawals could have resorted to the next closest thing—short-form videos on other American apps such as Instagram or YouTube—but they didn’t. Instead, they went out of their way to download and onboard an entirely Chinese platform—not just as a practical solution, but as an act of protest against the ban and the stance that if it’s from China, it must be bad.

It’s worth noting that RedNote is Chinese through and through. RedNote stands out as one of the few Chinese social platforms that doesn’t separate its domestic and international versions. This means it’s not a Westernized platform like TikTok, designed to appeal to Americans. Instead, RedNote offers a strategically built brand experience for Chinese users, featuring content driven by local trends, governed by domestic internet laws, and entirely in Chinese.

Even the app’s name is emblematic. The app’s name 小红书 (Xiaohongshu) directly translates to “Little Red Book”, a nod to Mao Zedong’s communist bible of sorts and literal little red book, that was once an unofficial requirement for Chinese citizens to own, read, and carry during the Cultural Revolution. This reference may go over the heads of some American users and the English rebranding of “RedNote” as it’s listed on the U.S. App Store avoids direct associations with China’s communist legacy. Still, for those already wary of Chinese influence, the name alone could be triggering—a Red Scare of the digital age.

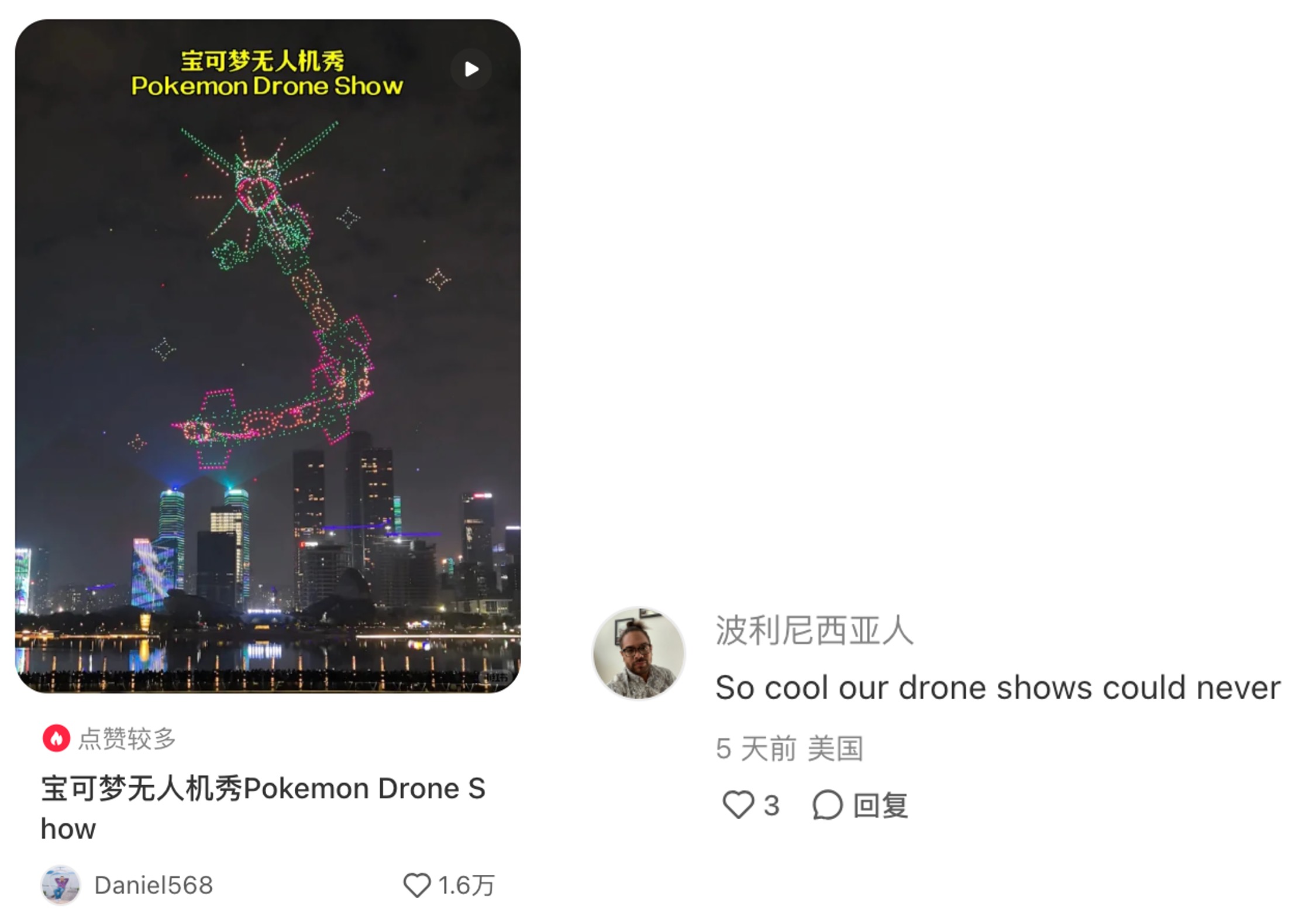

But for those Americans who actually joined RedNote, it was less of a “red scare” and more of a warm embrace. While much of the discourse around the TikTok migration centers on political resistance, the move to RedNote is also fueled by an unexpected cultural exchange—one that is equal parts satire and genuine curiosity. The American “TikTok refugees” have been met with a mix of warm hospitality and playful trolling from Chinese users, who jokingly call themselves “Chinese spies” and demand a lighthearted “tax” in the form of cat memes. This meme-fueled dynamic is fostering an organic connection between young Americans and Chinese digital culture, one that transcends the usual narratives of surveillance fears and trade wars. Instead of simply escaping a ban, these users are stumbling into an entirely new internet subculture—one where they are participants in a shared, evolving inside joke.

It can be a powerful experience for assumptions about China to be so intimately dismantled. For many Americans, it was the first time that they saw native Chinese content, interacted with Chinese people, or even had their first go at learning Mandarin. For some TikTok refugees, RedNote represented a testament to the human propensity for compassion—transcending language barriers and national borders.

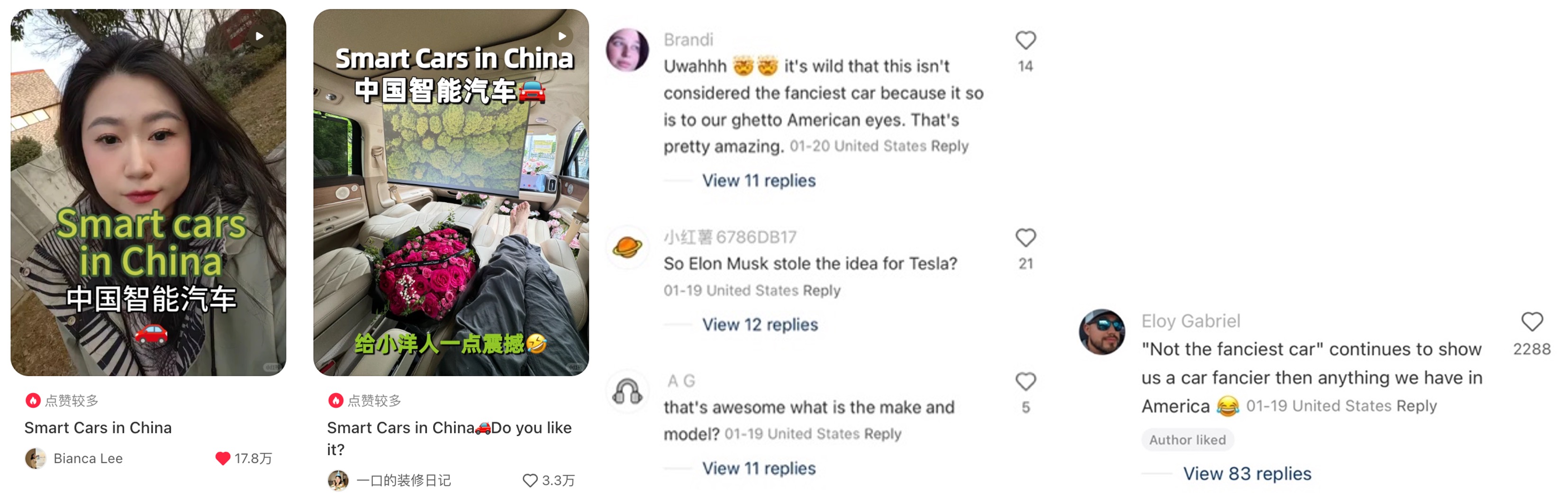

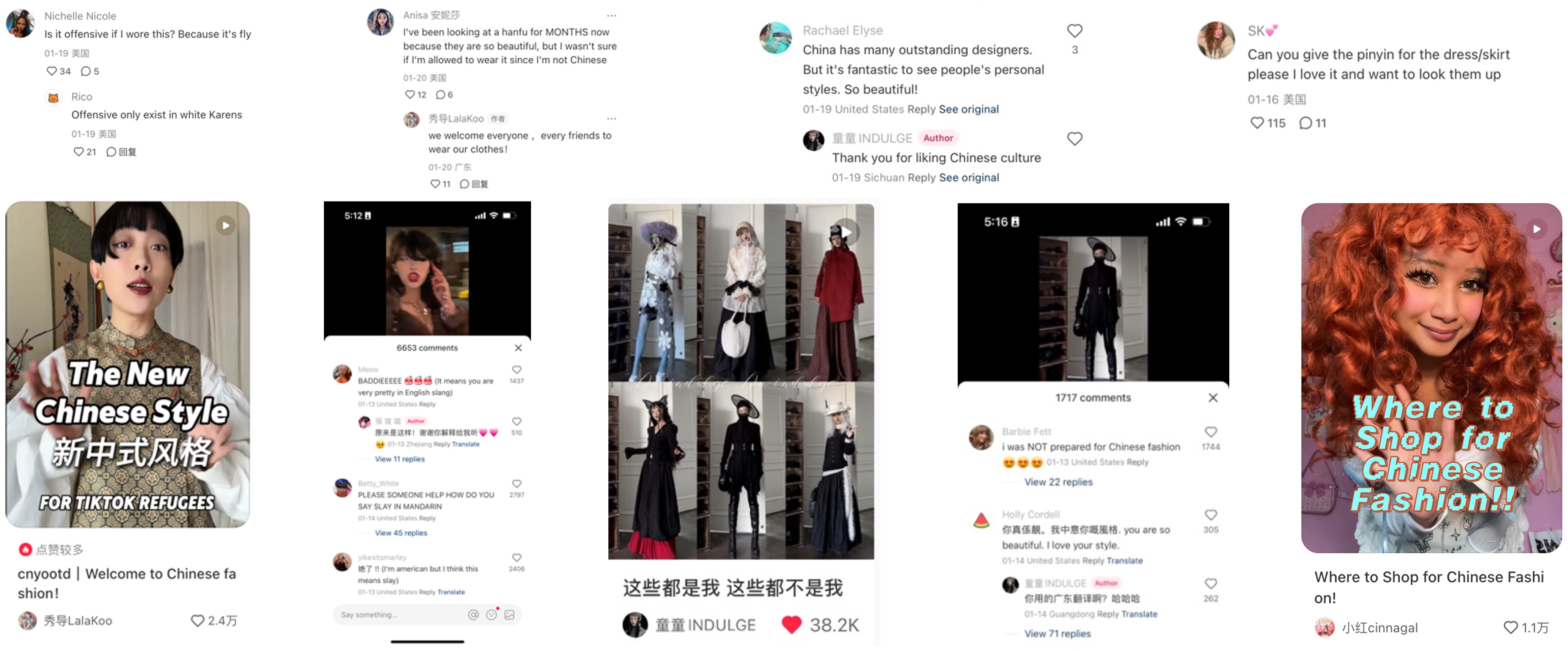

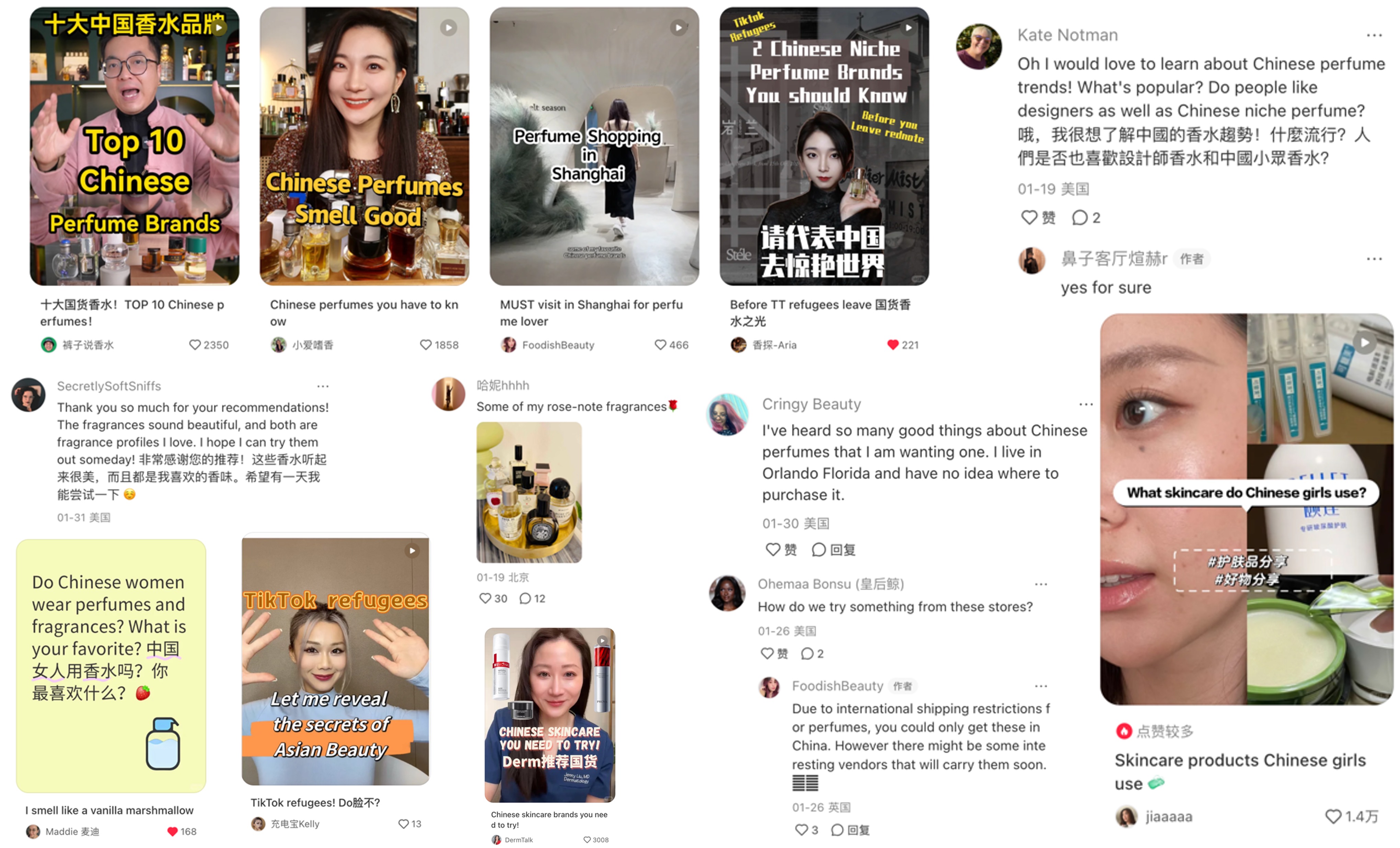

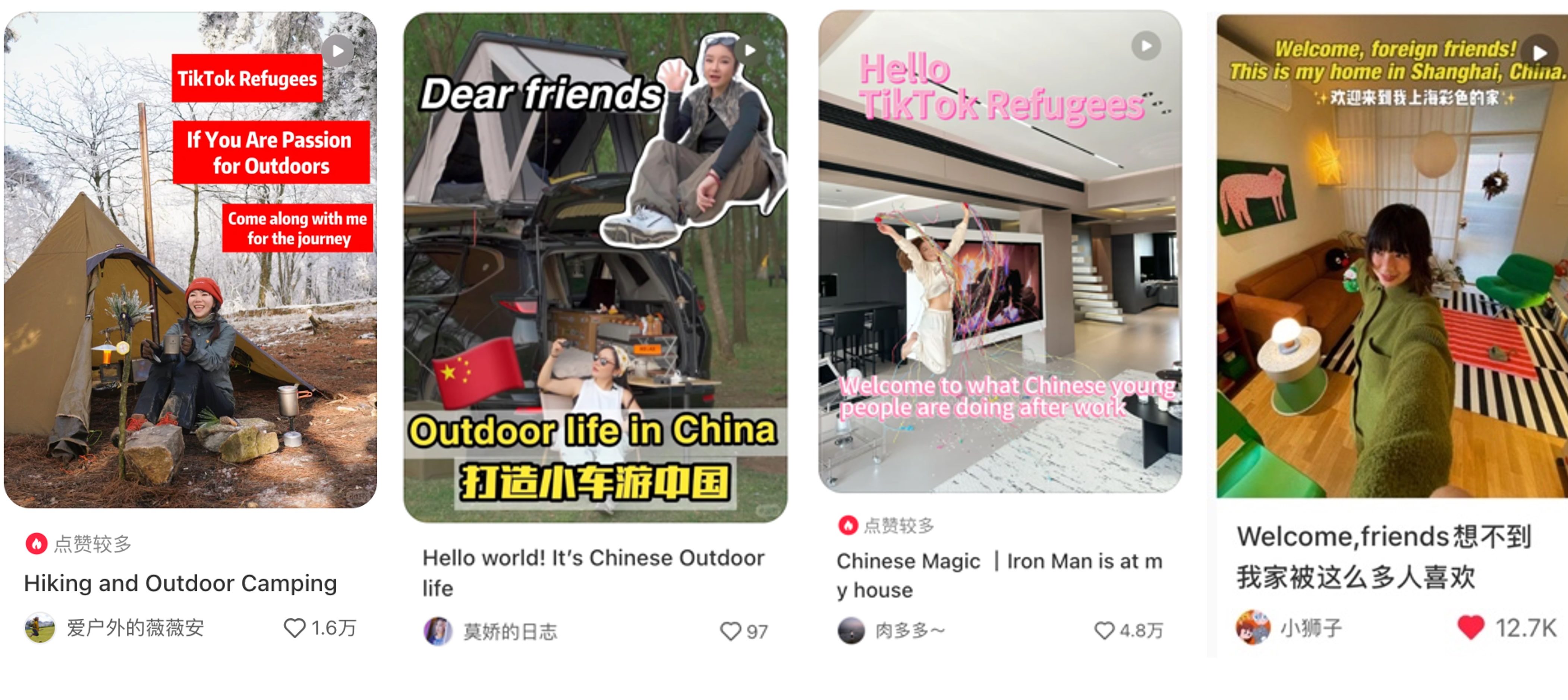

More than ever, younger Americans are seeing past the anti-China narratives. Americans’ emotions around Chinese products may have lingered between indifference, hesitation, and shame (See Table 1). But now, there’s a new wave of appreciation for Chinese culture— Chinese fashion, Chinese tech, Chinese homes, Chinese food, and the lifestyles of China presented to them person-to-person on RedNote.

2. Fashion: Chinese fashion influencers are serving on RedNote, with Americans in the comments praising their looks as fresher and chicer than what they expected. Chinese streetwear brands such as ROCKSTEADY, ESOTERIC THING, ROMANCATCHER have been mentioned in brand recommendation exchanges between Rednote natives and TikTok refugees.

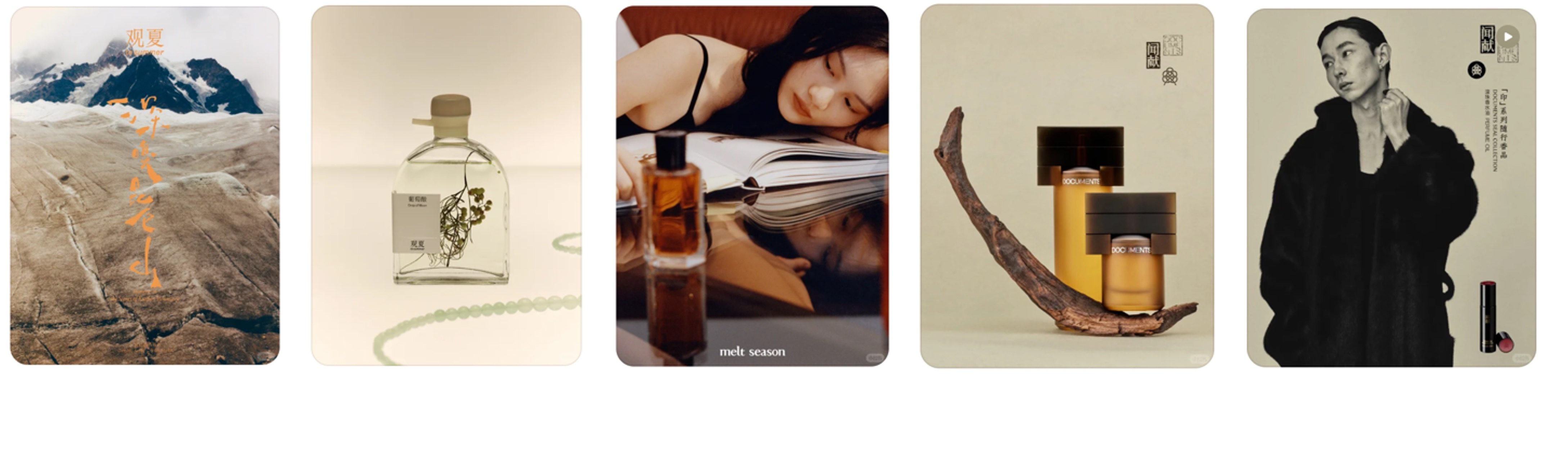

3. Beauty, Skincare, and Fragrance: The fragrance niche of RedNote attracted many TikTok refugees who expressed interest in buying Chinese fragrances, especially niche perfume brands. Video topics about skincare regimens and makeup also became hotbeds of cultural exchange.

4. Home & Lifestyle: The modern and hyper-functional design of Chinese homes is catching attention. Chinese interiors are inspiring American audiences, including upscale household goods, consumer electronics, and camping gear.

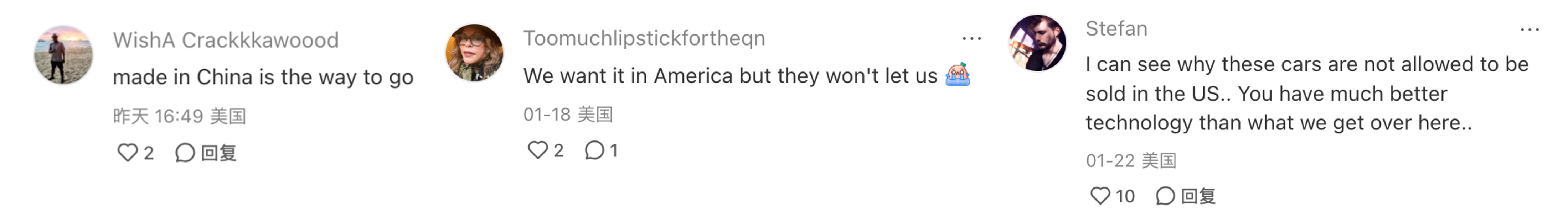

More and more, Americans see China as a hub for brand innovation and excellence. Over the next five to ten years, I anticipate a surge in Chinese brands gaining traction in the U.S., particularly among younger consumers. While the geopolitical climate is rife with tariffs and tension, the consumer’s choice still rings loud at a time when Chinese brands are thriving around the world. One American RedNote user notes “Overall I love seeing Chinese brands expanding into a more diverse and well-designed product spectrum.”

It’s only a matter of time before it’s mainstream for Americans to be frustrated at anti-China gatekeeping and ask themselves “why can’t we have nice things?” as one American commenter put

it when commenting on the affordable cost of a RedNote user’s self-driving Huawei EV.

One recurring observation among American TikTok refugees is the futuristic appeal of Chinese cities, cars, apartments, and overall lifestyle. It’s a positive stroke in China’s country branding that can be leveraged strategically when marketing Chinese products, granted they are branded effectively for American audiences.

Beyond benefiting from a futuristic association, Chinese brand iterations—whether tech, beauty, fashion, or home—could become a subtle form of value-signaling. Owning and endorsing Chinese brands might reflect a consumer’s sense of savviness, open-mindedness, and cultural fluency. For many, the emotions tied to purchasing Chinese products may shift from hesitation to pride and altruism (See Table 1). Buying Chinese products might reinforce confidence in consumer identity as savvy, ahead of the curve, open-minded, and smart enough not to buy into political fear-mongering. As Western netizens increasingly embrace Chinese platforms and products, these sentiments could become a notable characteristic of the next wave of consumer behavior.

The brands that act swiftly will be best positioned to capitalize on this development. For Chinese brands, the opportunity lies in strategically positioning themselves within this cultural shift. To effectively resonate with American consumers, they must craft brand narratives that align with evolving attitudes toward China. Key strategies include:

The shift is happening. The question is: which Chinese brands will seize the moment and redefine their place in the Western market? Stay tuned as we continue exploring brands shaping cultural narratives in our next BCTW feature , where we uncover another game-changer reshaping the industry.

References:

Bloomberg. “What Do Americans Think of ‘Made in China’?” Bloomberg, 17 May 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-17/what-do-americans-think-of-made-in-china-polling-latest?leadSource=uverify%20wall.

Council on Foreign Relations. “China’s Huawei Threat to U.S. National Security.” Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-huawei-threat-us-national-security.

Morning Consult. “Gen Z Favors Chinese Brands.” Morning Consult, https://pro.morningconsult.com/analysis/gen-z-favors-chinese-brands.

National Public Radio (NPR). “TikTok Ban: Secret Evidence and U.S. Classified Court.” NPR, 22 Aug. 2024, https://www.npr.org/2024/08/22/nx-s1-5085173/tiktok-ban-secret-evidence-u-s-classified-court.

NBC News. “New York State Bans DeepSeek Government Devices.” NBC News, 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/new-york-state-bans-deepseek-government-devices-rcna191510.

News Iowa State. “Made in China.” Iowa State University News, 3 Mar. 2016, https://www.news.iastate.edu/news/2016/03/03/madeinchina.

Pew Research Center. “In Their Own Words: What Americans Think about China.” Pew Research Center, 4 Mar. 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/03/04/in-their-own-words-what-americans-think-about-china/.

RAND Corporation. “TikTok Is a Threat to National Security—But Not for the Reasons You Think.” RAND Corporation, Aug. 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2024/08/tiktok-is-a-threat-to-national-security-but-not-for.html.

Reuters. “Over Half a Million TikTok Refugees Flock to China’s RedNote.” Reuters, 14 Jan. 2025, https://www.reuters.com/technology/over-half-million-tiktok-refugees-flock-chinas-rednote-2025-01-14/.

Rosenbaum, Eric. “1 in 5 Corporations Say China Has Stolen Their IP within the Last Year: CNBC CFO Survey.” CNBC, 1 Mar. 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/28/1-in-5-companies-say-china-stole-their-ip-within-the-last-year-cnbc.html.

Sloan Review MIT. “How Chinese Companies Expand Globally Despite Headwinds.” MIT Sloan Review, https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-chinese-companies-expand-globally-despite-headwinds/.

Time. “Temu App Complaints.” Time Magazine, 2024, https://time.com/6243738/temu-app-complaints/.

Time. “Shein, Climate Change, Labor, and Fashion Controversies.” Time Magazine, 2024, https://time.com/6247732/shein-climate-change-labor-fashion/.

The New York Times. “Cambridge Analytica Scandal Fallout.” The New York Times, 4 Apr. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-scandal-fallout.html.

BBC News. “China’s Economic Influence and Western Response.” BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-34932800.

Forbes Agency Council. “Why Brand-Building Is China’s Key to the Future.” Forbes, 30 Aug. 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2018/08/30/why-brand-building-is-chinas-key-to-the-future/.

The Robin Report. “Three New Chinese Brands That Should Worry You.” The Robin Report, https://therobinreport.com/three-new-chinese-brands-that-should-worry-you/.

Daily Mail. “Meta and Google Help Congress Ban TikTok in the U.S.” Daily Mail, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-13400521/meta-google-help-congress-ban-tiktok-us.html.

American Enterprise Institute. “The Rising Risk of China’s Intellectual Property Theft.” American Enterprise Institute, https://www.aei.org/articles/the-rising-risk-of-chinas-intellectual-property-theft/.

YouTube Videos:

Sarah Bourek

Insights & Strategy Consultant, Labbrand New York

A Labbrand Group Company © 2005-2024 Labbrand All rights reserved

沪ICP备17001253号-3* Will be used in accordance with our Privacy Policy

To improve your experience, we use cookies to provide social media features, offer you content that targets your particular interests, and analyse the performance of our advertising campaigns. By clicking on “Accept” you consent to all cookies. You also have the option to click “Reject” to limit the use of certain types of cookies. Please be aware that rejecting cookies may affect your website browsing experience and limit the use of some personalised features.